Book Review: Landscape in Concrete by Jakov Lind

First appeared in Three Percent

We meet a familiar angst-ridden Russian early in the pages of Jakov Lind’s novel Landscape in Concrete: Dostoevsky’s Underground man surfaces in the guise of Gauthier Bachmann to here tread the desolate earth of the Ardennes during WW ll. No longer confined by inertia to his wretched little room, this protagonist is on the road — a bleak, inhuman, carnage-scarred road — blindly journeying in search of meaning and identity. It’s as if the contents of a diseased mind have spilled out into the real world.

And indeed, after witnessing unbelievably shocking scenes, it is hard to regain a grasp on real, ordinary life. Such is Bachmann’s lot. A sergeant in the German army, he has, as the book begins, just fought in a battle at Voroshenko and seen his entire regiment slaughtered, sunk in a quagmire of blood and mud.Throughout the book, Lind then dips us, episodically, into the hell of Bachmann’s post-traumatic existence and his logical/illogical flight back to what he knows. Against “human” nature he wants willfully to expose himself again to the horror of war; in this sense perhaps he is ill: unwilling or incapable of caring; unable to hope. He has seen friends and countrymen blown to bits; what reason is there to live? He is filled with uncertainty too: about what constitutes a “man,” whether or not he is one, whether he is diseased, dead or alive, real or make-believe. Returning to the simple order that the army offers is perhaps all he has to hang on to, because good, honest, stable “normal” life and relationships aren’t found in the world he now inhabits.

Voroshenko renders Bachmann “unfit for duty.” Despite this, he journeys throughout the Ardennes in quest of a fighting unit he can once again join; to which he can “belong.” Neither “spiteful nor kind, rascal nor honest man, hero nor insect,” Bachmann stoically sinks into depravity, abdicating responsibility for his actions, numbly stumbling around, Lear-like, encountering and succumbing to the wishes of evil, indecent characters, willing to do anything to fill the void.

Bachmann, unlike the Underground Man, acts. But he acts in the wrong way. No one, Victor Frankl tells us, in Man’s Search for Meaning, has the right to do wrong. Bachmann does wrong. He acts indecently.

The first person he meets is a mole of a man, Xaver Schnotz, who has deserted his nearby unit after poisoning a kitchen worker to death with “piptol.” Here, exampling Lind’s blunt descriptive powers, is how it works:

“Your eyes crawl out of their sockets like snails and they can’t get back in. (He tittered.) Your tongue gets stiff and hard as shoe leather, black leather, and your nostrils contract so tight you couldn’t stick a needle in, they close up as if there’s never been any holes, your ears hang down like dry leaves, and your hands cramp up like this, they turn into claws (he demonstrated, tittering again), and then, very very slowly, you suffocate. That’s piptol, friend.”

Starving, Bachmann and Schnotz engage in a frantic, hilarious fight over who gets to eat the liver of a freshly bagged chicken. The next day Bachmann turns Schnotz back into the authorities in hopes of securing a commission for himself. Commander Von Goritz tests Bachmann by ordering him to execute a saboteur who looks “strikingly like Schnotz.” Bachmann obeys, and, despite guilt, justifies his actions, Nuremburg-style, by telling himself that he is just following orders. His warped enterprise, the gaining of purpose through re-enrollment in the army, trumps any humane instincts he may have once owned. Whenever behavior doesn’t align with belief, self-hatred will follow, and illness is sure to be near; as Dostoevsky put it: can those who enjoy the feeling of their own degradation possibly have a spark of respect for themselves?

The grizzly slide into depravity continues as Bachmann is later ordered to kill Baron Elshoved and members of his family:

Cut him open, came Halftan’s placid voice. With his left hand Bachmann held the back of Thor’s neck and with his right cut him open from throat to abdomen. He had to step aside quickly, for the blood gushed like a spring when the stone is taken away. A man is full of blood, the way a balloon is full of air. It was always fun to burst balloons, it made a bang, it was exciting. A man doesn’t make any bang. Thor wheezed and collapsed. The knife had gone through part of his windpipe. Bachmann let him down slowly with his left hand. Woudn’t want the poor kid to fall on his head.

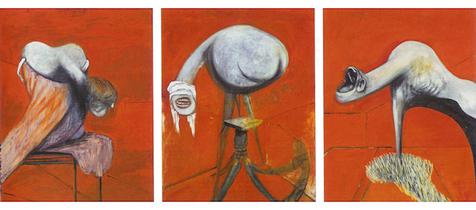

Here is the written equivalent it seems of Francis Bacon’s raw, Godless depiction of man as no more than blood, guts, and intestines in his painting Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion.

Bachmann is calm after the abattoir. But he has no monopoly on depravity. Others in fact descend deeper into the pit, showing us “the plague called man.” The remaining daughter Gudrin, for example, steps forward, unafraid, expressing pleasure at her family’s slaughter . . .

“That’s what I’ve always longed for . . .” and a willingness to be taken. Though Halftan had thought of it often, of taking her by cajolery, by force, “now that there’s nothing more to fear, neither parents nor brothers, now that I could kill her, I don’t want her any more.”

The nadir is reached at the end of the book, as Bachmann, after an air-raid shatters a blissful togetherness with his girlfriend, ravishes her. “Behind closed eyelids he saw the brown Cyclopses of her breasts, he slid over the bloated white body, grazed the reddish weeds that grew out of the hollow, and dwelt at length on the fattened turkey backs of her haunches.”

Landscape in Concrete is filled with appropriately harsh, disturbing passages like these. At times the similes don’t quite work, “Bachmann was heavy and shapeless, like the clouds that covered the fields . . .” but for the most part they do, and there are passages in this book which affect, as Kafka tells us important work should, “like a disaster, that grieves us deeply, like the death of someone we loved more than ourselves, like being banished into forests far from everyone, like a suicide.”

Read and be affected by it, but as an antidote, remember that life is not what happens to us — but rather, how we choose to respond.