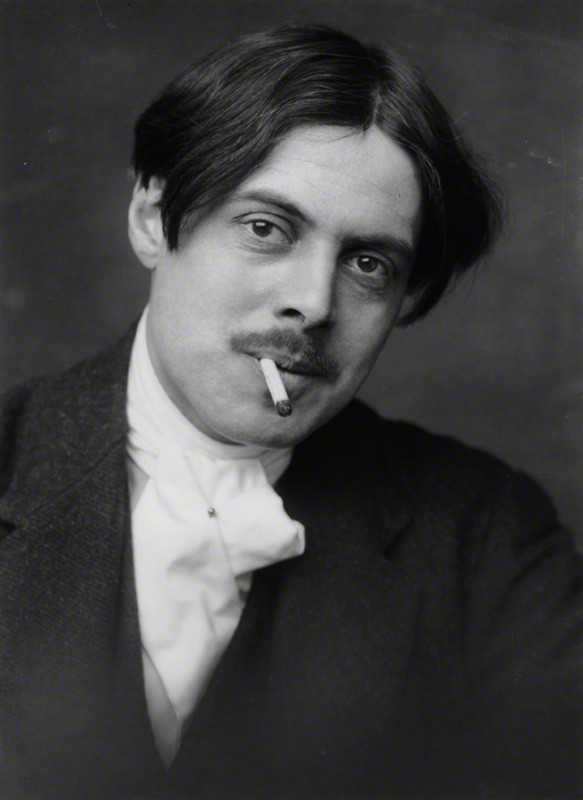

Wyndham Lewis: overlooked scourge of mediocrity

First appeared in The Guardian

Wyndham Lewis's thorny persona means grudges are being held beyond the grave and we still don't recognise the extent of his talent

"A hundred books of fiction every month are referred to by eminent critics in language of such superlative praise that, were it the work of Dante that was in question, it would be adequate, though a little fulsome."

Author and artist Wyndham Lewis said this in 1934. Sir Howard Davies quoted Lewis last year when chairman of the Booker Prize committee, suggesting that critics should maintain a less cosy relationship with their subjects.

Cosy is one thing Lewis definitely was not. His prickly public comportment, and where it got him, provide a sobering lesson on how not to behave if you want to get ahead in the very personal profession of publishing.

According to Lewis, the "era of puff and blurb in place of criticism" started with Arnold Bennett, when he "turned reviewer/star salesman for the publishers". Lewis portrays Bennett in The Roaring Queen as representative of the commercialisation of literature - the transformation of book-publishing into big business - a business in which Lewis wasn't about to participate. Hostility to puffery, a proclivity for argument, and brilliant literary insight all boil up in Lewis to explain why he went out of his way to criticise the establishment.

After wowing the world as a writer and painter, Lewis went to war - unlike the other "Men of 1914": T S Eliot, Ezra Pound and James Joyce. The experience embittered him. He felt the war destroyed cultural values, demoralised the world and robbed him of time. It had also opened his eyes to "the usurious economics associated with war-making".

During the 20s, Lewis developed a public persona: a gadfly known as 'The Enemy' who shot mercilessly at popular ideas and art, the legacy of the Romantic Movement, and left-wing artists and intellectuals. He even went so far as to state the case for Hitler, a position he later recanted after visiting Berlin in 1938, but only after the damage had been done. Few understood that his motivation at the time was avoidance of another war.In literature he fired bullets everywhere. Almost every author of note gets hit at some point during the period between the wars. Virginia Woolf, for example, is attacked as much for her association with art-critic and painter Roger Fry (who Lewis believed had wronged him early in his career) as for literary poverty. Lewis accused Woolf of thieving from James Joyce, calling Mrs Dalloway "an undergraduate imitation of Ulysses", "lacking the realistic vigour of Mr. Joyce, though often the incidents in the local 'masterpieces' are exact and puerile copies of the scenes in his Dublin Drama." Time and Western Man wails on everyone: Bloomsbury, the Sitwells, and "romantics" D H Lawrence and Gertrude Stein, but also Joyce, and close friends Pound and Eliot.

While there is definitely a healthy egalitarianism at work in his dispensation of criticism, these blunt, bracing truths buttered no parsnips. Despite writing 23 books between the wars, editing two reviews (The Tyro and The Enemy), and producing some of his most celebrated paintings (portraits of Edith Sitwell, Pound and Eliot), Lewis was far from prosperous.

He had no steady employment and had to survive on freelance journalism and publishers' advances. His public explosions and take-downs had consequences. Libel laws ensured a regular stream of suits and threatened suits, meaning that books had to be withdrawn. The press was hostile or boycotted reviewing his work. He had to bring out The Apes of God first under his own imprint.

His life is proof that prodigious, widely recognised talent isn't enough to secure reputation: ass-kissing and fib-telling, flattery and tongue-biting are often required to make careers. The alternative, for those incapable of sycophancy is squalor: the kind in which he lived, blind, during the final years. The irony is that despite all the public histrionics and bombast, Lewis was a strikingly private, thoughtful man, who was able to maintain important friendships throughout his lifetime. He died aged 74 in 1957.Recently there has been renewed interest in Lewis and his work, complete with the National Portrait Gallery's stamp of approval. It will be running a major retrospective of his portraits in from July to October.

About time too, for, as Jeffrey Meyers puts it at the end of his biography The Enemy, "Lewis's range of knowledge and intellectual vitality, his gale-force energy and daring honesty, his vigorous experimentation and fighting spirit, his caustic wit and analytic ingenuity, his whip-cracking prose and astonishing invention are unmatched in the twentieth century." National Gallery notwithstanding, it seems if you want to tell the truth without compromising, you have to die poor and have your literary immortality postponed for at least 100 years.